Female Marble Statue in Gibbs South Carolina Art Gallery

In the late nineteenth century, it was widely believed that women could not be sculptors given their supposed preference for colour, and thus for painting. It was besides causeless they were at a disadvantage in terms of concrete strength. If they did manage to produce sculpture, this was assumed to be derivative since they were believed to be incapable of originality.

A specially spinous comment appeared in an 1896 interview with George Frampton who was sure that: 'no thing how poetic the idea, how ethereal the finished bas-relief or statue... the art of the sculptor in its noblest form demands strenuous labour and then that you may regard it equally existence tolerably secure from invasion by the new woman, or the mere dilettante; for it is a most perfect instance of fine art inextricably allied with fine craft.'

Apart from such regrettable attitudes, a applied obstacle for women sculptors arose from expectations concerning their gender. They were non usually expected to follow a career, and information technology was taken as a given that any creative impulses would exist fulfilled through marriage and family unit responsibilities.

Despite these difficulties, a meaning number of women were working as professional sculptors. However it was depressingly frequent to see writings that focused on their gender, resulting in trivialising descriptions of incidental domestic and anecdotal issues that would rarely be the case in writings on their male colleagues.

We might suppose that such times have passed. Still in a 1988 BBC Radio Solent broadcast with Mary Spencer Watson (1913–2006) the interviewer described how he could come across in his listen a vision of a 'petite 12-twelvemonth-old girl working away with massive tools on a cracking block of stone', referring to Spencer Watson's early encounters with stone carving in Dorset'due south Purbeck quarries.

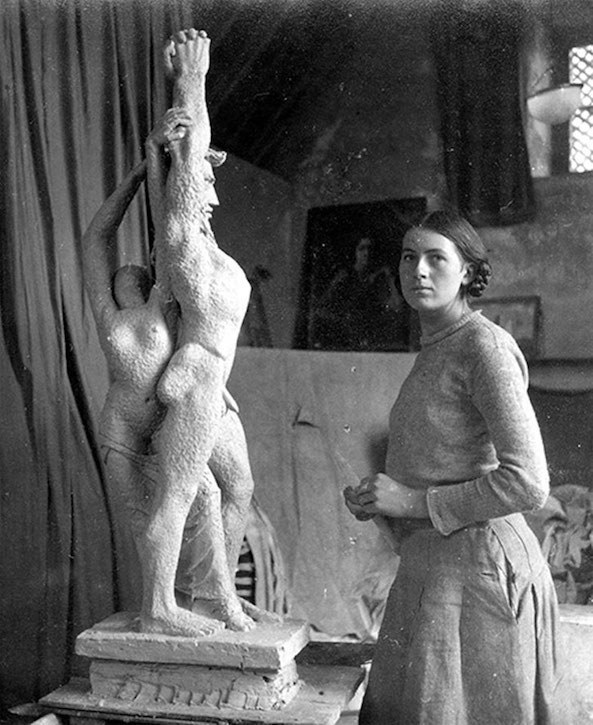

Mary Spencer Watson in her studio

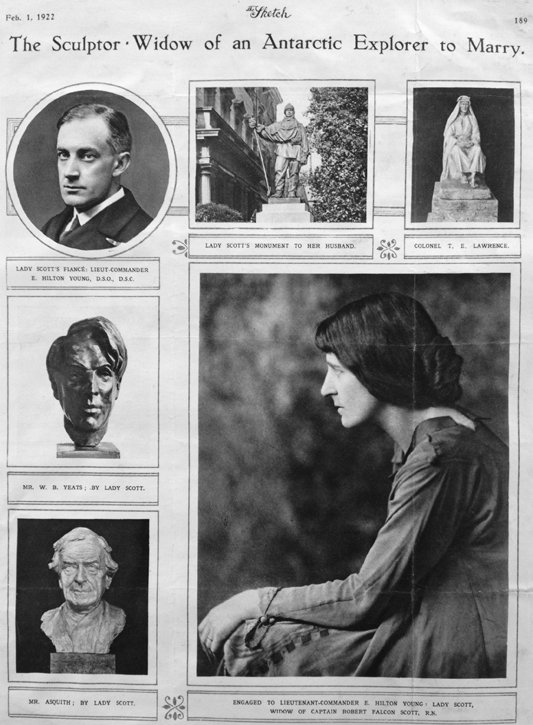

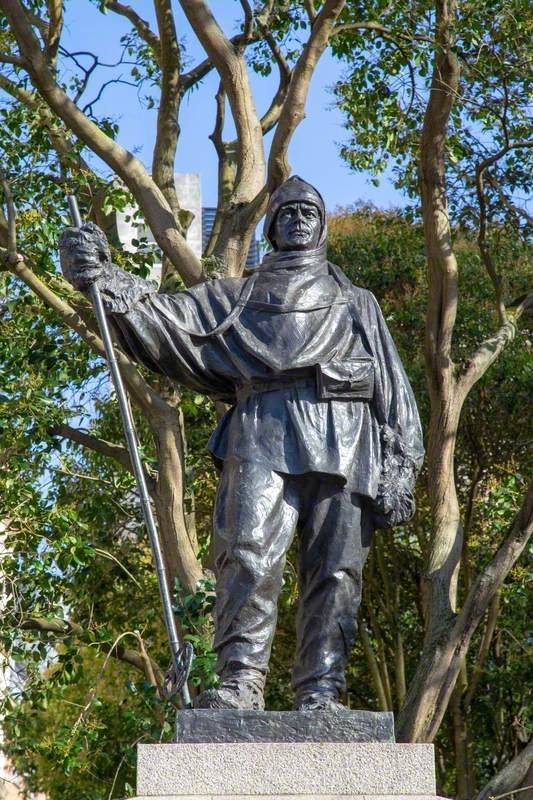

The continuing novelty of the female sculptor ran through numerous manufactures, one example from 1922 in The Sketch announcing that Kathleen Scott was to remarry afterwards the death of her starting time husband Antarctic explorer Robert Falcon Scott in 1912. Her second married man was politician Edward Hilton Young, who was created Baron Kennet in 1935, and who extended her network of influential individuals in the political and creative spheres.

'The Sculptor Widow of an Antarctic Explorer to Ally'

published in 'The Sketch', 1st February 1922

In the page from The Sketch, Scott is shown surrounded by her sculptures of prominent male person sitters, in the centre of which is a portrait of her fiancé. Scott's social status would keep to preoccupy reviewers.

Despite the quantity and range of accounts which had trivial to say about women sculptors' work, they were part of the expansion of sculpture in the belatedly nineteenth century onwards. The emergence of the so-called 'New Sculpture' saw a shift in manner towards an emphasis on movement and realism, departing from classical precedents. This development too led to a questioning of the boundaries between 'fine' and 'decorative' art.

Ane of the near notable results was the emergence of the statuette, which was promoted as an affordable way for the middle classes to demonstrate their sense of taste in creating fashionable homes.

For women sculptors, the statuette afforded a bully opportunity to produce small-calibration work, and their work in this area does seem particularly distinctive. Statuettes made past male sculptors were frequently reduced versions of a monumental figure, whereas those made past women were mostly conceived to calibration from the outset.

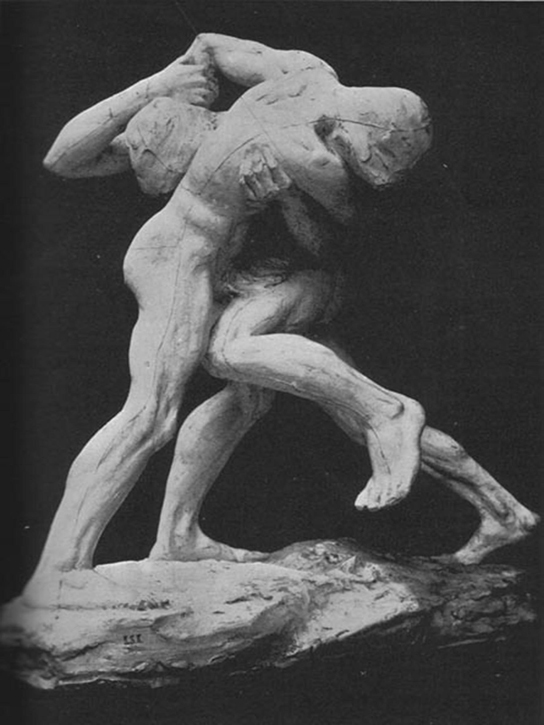

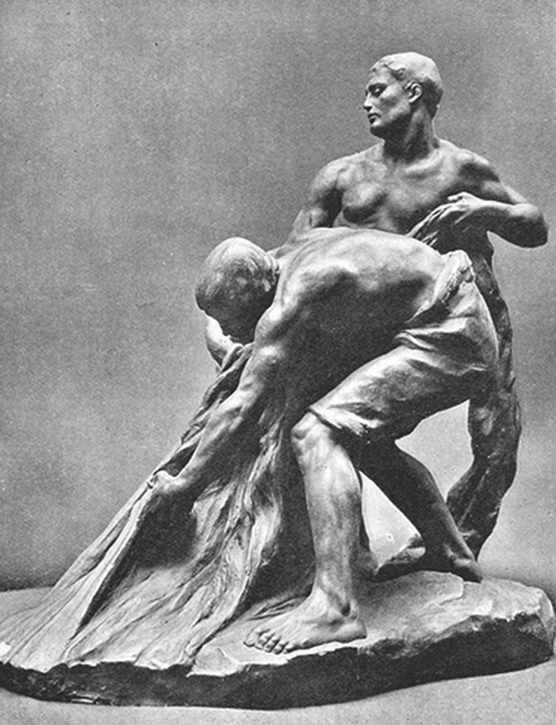

Wrestling Boys

1897, plaster statuette by Ruby Levick (c.1872–1940)

This sculpture by Ruby Levick has been likened to Frederick Leighton's influential Athlete Wrestling with a Python (1877), likewise reproduced equally a statuette.

The intertwining of the limbs in the Levick work encourages the viewer to expect at the sculpture from a variety of viewpoints, and thus to move in closer. Levick's studies of male athletes were particularly admired, such as the statuary statuettesBoys Angling and Fishermen Hauling in a Cyberspace.

Fishermen Hauling in a Net

1900, plaster statuette past Ruddy Levick (c.1872–1940)

Margaret Giles' statuette Hero (1901) moves abroad from conventional representations of the female nude as passive.

Hero

1901, bronze sculpture by Margaret Giles (1868–1949), private collection

Indeed, in that location are some resemblances to a Michelangelo figure in the force of the effigy, merely at the same time, the work rejects classical features of stillness and rest.

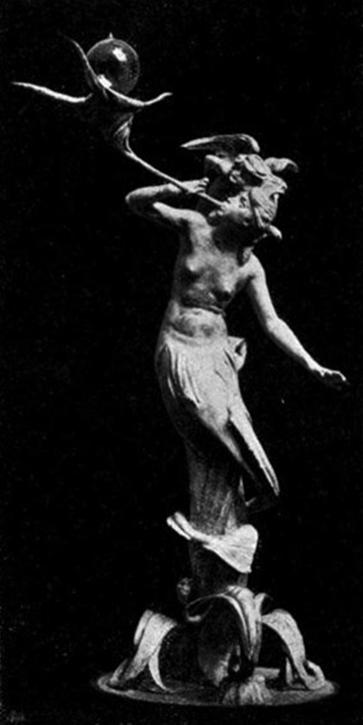

Lilian Maud Wade's statuette Victory, shown at the Royal Academy in 1907, was possibly a maquette for a significant memorial.

Victory

c.1907, statuary sculpture past Lilian Maud Wade (1870–1923)

Some other of her winged figures can be seen on this funerary monument to 2nd Lieutenant Rex Moir (1898–1916) and his father Sir Ernest William Moir (1862–1933) in Brookwood Cemetery, Woking.

Monument to 2nd Lieutenant King Moir (1898–1916), and His Father Sir Ernest William Moir (1862–1933)

before 1923, bronze by Lilian Maud Wade (1870–1923), Brookwood Cemetery, Woking, Surrey

Rosamund Praeger (1867–1954) was active in the Northern Ireland art scene. A specially cute work is her statuette of the Irish-built-in Saint Fiachra.

The statuette form was as well ideal for conveying a sense of intimacy in mother and kid subjects, and somehow their small format allowed for the possibility that such works might be viewed equally both secular and religious.

Lucy Gwendolen Williams' bronze Queen of Dreams is a particularly successful work.

Queen of Dreams

1905–1906, bronze, dark brown patina on an onyx marble base of operations by Lucy Gwendolen Williams (1870–1955)

A much afterward work past Elsie March (1884–1974) shows the longevity of this subject field and modest format, dating from 1950.

Apart from working with the statuette equally a high-quality artistic artefact for the domestic interior, many female sculptors also worked within the surface area of applied fine art. These included Florence Steele (1857–1948) who likewise produced borough regalia equally in her 1912 trophy, in a format like a miniature memorial.

Bays for Buffs, in Memory of the South African State of war

1912, metalwork by Florence Steele (1857–1948)

Adèle Hay (agile 1897–1904) produced an exquisite bronze door knocker.

Door Knocker in the Form of Saint George and the Dragon

c.1899, statuary by Adèle Hay (active c.1897–1904)

Many of these women produced pieces that harnessed the statuette with a functional object such as an electrical lamp. A peculiarly svelte example was made by Esther Mary Moore (1857–1934) in 1900.

Electrical Lamp

1900, bronze by Esther Mary Moore (1857–1934)

At the other end of the sculptural scale, many women sculptors produced highly successful monuments. These were by no means the sole province of male practitioners.

Ellen Mary Rope (1855–1934) often worked in the format of low plaster reliefs, many of them personal memorials.

Ane impressive example was a composition that depicted an affections sounding the terminal trump which Rope reworked on at least iii occasions. The initial committee in 1890 was for a memorial to Mrs Mary Anne Moberly, wife of George Moberly, Bishop of Salisbury Cathedral.

The Affections of the Resurrection

c.1902, marble by Ellen Mary Rope (1855–1934), Salisbury Cathedral

Given its shallow relief, the illusion of depth is impressive. Depressingly, such is the fate of much sculpture made by women, that in order to photograph this work in Salisbury Cathedral I had to accommodate for a cupboard that was placed in front of information technology to be moved aside.

Frances Bessie Burlison'south impressive Beaumont Higher state of war memorial was unveiled in 1921.

Beaumont College War Memorial, Windsor

1921, bronze figure by Frances Bessie Burlison (1875–1974), ashlar stone curvation by Giles Gilbert Scott and Adrian Gilbert Scott

The memorial comprises a Portland stone arch framing a life-size sculpture of Christ crucified, beneath which are the names of the dead, the whole mounted in a higher place an altar, symbolic of sacrifice. Burlison sculpted the bronze effigy and the arch was designed by Giles Gilbert Scott and Adrian Gilbert Scott.

Mary Pownall Bromet (1862–1937) likewise demonstrated a technical virtuosity which led to several commissions that required emotive figures such every bit those comprising her 1928 Watford War Memorial, later renamed Peace Memorial.

Watford Peace Memorial

1928, bronze by Mary Pownall (1862–1937)

Nether each of the figure, from the left, are the words 'Victory', 'To the Fallen' and 'To the Wounded'. The 3 male person nudes show the influence of Rodin and are designed to represent the iii main aspects of war.

Many female person sculptors were able to engage with public commissions. This despite the fact that they more often than not did not have the benefits enjoyed by their male person colleagues such as being part of the professional and institutional networks.

There were many British women sculptors from the mid-nineteenth century onwards, despite all the difficulties they might experience. When they did succeed they were often characterised as the exceptions amidst their sex.

Female person Dancer

Mary Spencer Watson (1913–2006)

Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Gild

The American writer Mary Fanton Roberts (1864–1956) pinpointed the cultural and social constrictions experienced past female artists:

'The question is... not one of sexual activity discrimination, but of fundamental sex variations in expression... true fine art must forever reverberate existing conditions of life... The monk and the non-conformist akin are jump back from productive art by the limitations of renunciation; the scientist by the limitations of mathematics; the imperial man by the limitations of formalities. And and so, peachy art does not flourish in the monastery, in the laboratory or in the palace. For it has always demanded freedom, the liberty to think straight and to see articulate, a perfect freedom of observation and experience... woman, the globe over... has not this freedom.'

This argument is a remarkable precursor of the arguments made by Linda Nochlin in her 1971 essay 'Why have in that location been no smashing women artists?', in which she pointed to the absence of professional artists from the aristocracy whose fourth dimension was committed to running big estates, or from women whose function information technology was to raise and care for families.

Given the obstacles that women sculptors faced, their achievements were significant, not the least since they oftentimes worked lone and often with the additional responsibilities of being a wife and mother.

In that location are numerous references to women sculptors in catalogues and exhibition reviews, only trying to locate their work is a huge challenge. Art UK's work represents a meaning step frontward in revealing many professional person female sculptors.

Pauline Rose, author of Working confronting the Grain: British Women Sculptors c.1885–1950

More stories

Artworks

Learning resource

Source: https://artuk.org/discover/stories/a-look-at-britains-neglected-professional-women-sculptors

0 Response to "Female Marble Statue in Gibbs South Carolina Art Gallery"

Enregistrer un commentaire